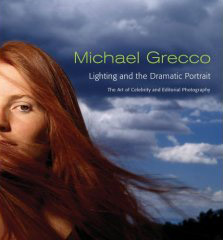

Having been a good boy this year (or, at least, not getting caught) I got a few things on my Christmas list. One of those items was Micheal Grecco's book,

Lighting and the Dramatic Portrait.

I know that many of you are ahead of me on this one. And there has been a fairly spirited discussion on the book on the

Flickr Strobist group.

But I have finally read the whole book (in chunks each night before going to bed since Christmas) and wanted to check in with my two cents worth on it. I'll start by saying what the book is not.

It's not a beginning lighting book. There isn't enough info on beginning lighting to start from zero and have a good sense of the technique and the craft. Ditto the info on cameras.

Unfortunately he kills fully a quarter quarter of the book speeding through these two topics. I suspect there was some arm-twisting from the publisher and/or editor, as this is clearly not the main thrust of the book. He gets through it quickly, with too much info for the experienced shooter and not enough for the beginner.

If you are looking for a general book on lighting, this should not be your first read. Maybe not even your second. That said, when he gets to his strength, the book really earns it's keep.

The main body of LATDP is, for me anyway, a treasure trove of info. I have already highlighted the bejesus out of my copy, and will probably make more notes on the second run-through.

Many of you have given glowing reports of the book. From others:

Eh, not so much. I think the book is refreshingly atypical in its approach, and wanted to report on what I have learned.

His main premise is one of learning - and then eschewing - the classic portrait lighting techniques. This is a view that I have been coming around to on my own over the last few years.

I look at it this way: Why go to the trouble to set up lights just to end up with a technically good, yet nauseatingly predictable photo?

I mean, do you ever walk into a place and see soft light coming in from twin 45-degree angles and think,

man, that's a hot look?

Of course you don't. You notice edgy light. Back light. Beams. Spots, Mottled shadows doing cool things. That kind of stuff. So why is it that when we first dive into off-camera light, we go for well-exposed, classic, predictable, boring light?

That isn't the kind of light what stops us cold when we are paging through a magazine. But we sure do go to a lot of trouble (and expense) to make it.

I am as guilty as the next person. Well, more

was as guilty as the next person. After all, it is "safe" light. And it does look very technically competent, for lack of a better word.

Having just described "Classic" portraiture lighting in the previous paragraph, here's what Grecco has to say about it:

"In most cases when I see this kind of lighting, I get a hairball in my throat. Not only of how predictable it is, but because of what it generally represents: slick, pedestrian lighting that is to me, schlocky!"

And how.

This guy does not just walk the walk, either. He goes on to break almost every lighting rule in the book. And if you think about this for a sec, how could you ever hope to stand out in a crowd

without taking this approach?

Don't get me wrong. The crowd is a pretty safe place to be. For weddings, corporate shooting, events, etc - that's where the steady paychecks are.

Do I ever just bang out a classically lit portrait? Sure. All the time.

Why? Usually it is a time constraint - I know classic is safe, and I may not have the resources to go for multiple looks. Also, it frequently fits within the editorial mandate in that I do not want to inject too much vision into something and divert attention from the subject itself, which is the real story.

But more and more, I find myself tired/bored/impatient/downright angry with the idea of "expected" lighting. I think I am spending more time and energy taking chances with my light. And when I do I am generally happier with the result.

Grecco gives example after example of how he chooses to break the rules while on assignment.

One of my favorite examples - and so simple - is how he lit the NYPD Blue stars from the bottom with a hard light to get the upside shadows. (Click above to see bigger.) Then he gobo'd the light from the two guys' faces, then lit the faces from the top with gridded lights.

Well, of course. Why didn't I think of that? In a small setting, you end up with scener mood light coming from below and face light coming from above - both from the camera's horizontal axis.

That's not something you're just going to happen upon. That is the product of always looking for a way to break the rules and create a "look."

I really like the guy's problem solving, too. His is almost all location work, so he gets thrown a lot of curve balls. But Grecco can hit a curve.

Shooting a portrait of a man in a stainless steel freezer, he wraps the area in front of the freezer in seamless white background paper and throws his lights into that for smooth, gradient reflections. Then he shoots through a slit in the paper. But he's not done yet.

On top of that, he grids the guy's face, to pop it. Then, on the lights illuminating the freezer, setting he uses not one but several various shades of blue on the different flashes. This guy is going beyond using blue to connote "cold" and using a whole palette of blues to add layers of depth and three-dimensionality.

Take ringlights for example - something I am starting to play with for the paper's Varsity section. He uses them not as a main light, but as perfect, lens-axis fill to bring dramatically angled light into a contrast range that his camera can handle.

Well,

duh. But not that I ever would have thought of that on my own.

He spends a decent amount of time on technique and anecdotal stories about the care and feeding of subjects. This bedside manner stuff is so crucial to producing killer portraits. Great portraits aren't taken - they are given.

Realistically, I will never have Grecco's budget, his assistants, his technical support or his tax bracket. But I also won't have his pressure. Nor will I have subjects with super-inflated egos like the ones he has to deal with.

His step-by-step descriptions of how he has gotten some of these people from "what they want to do" to "what he wants them to do" is valuable stuff to a real-world, working stiff like me.

To read the book, you'd think he regularly gets on his knees and begs for just five more minutes to squeeze in a concept that the subject may have nixed in favor of their own. Or maybe time constraints were bearing down on him. Whatever.

When it comes to making the shot he wants to make, this guy is water finding downhill. Whatever it takes.

While I do not work at Michael Grecco's professional altitude, I am pulling stuff from this book that I will use nearly every day. If I were a corporate shooter, it might apply less to me. Safe is big bucks in the annual report world.

If I were shooting just for me, I'd be eating this stuff up and darn-near wearing it out in practice, in hopes that before I used it all up the thought process might rub off on me.

But shooting environmental portraits for sports and biz at The Sun, and shooting illustrative projects for features, the inspiration from this book will last me a long time.